Feature: Pooling Their Talents

A ship has sunk in Boston Harbor, along with its cargo of hazardous chemicals. Remotely operated underwater vehicles (ROVs) are dispatched to map the area, take water samples to test for leaks, and salvage the wreck.

A ship has sunk in Boston Harbor, along with its cargo of hazardous chemicals. Remotely operated underwater vehicles (ROVs) are dispatched to map the area, take water samples to test for leaks, and salvage the wreck.

Substitute a college swimming pool for the harbor and you have an actual exercise from the Sea Perch Institute, which trains teachers and, through them, middle and high school students to build and operate ROVs.

Created in 2003 by the Sea Grant College program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and funded by the Office of Naval Research, Sea Perch “makes science and math concepts relevant” while helping students acquire real-world problem-solving skills, says Bill Andrake, a science teacher at Swampscott Middle School in Swampscott, Mass.

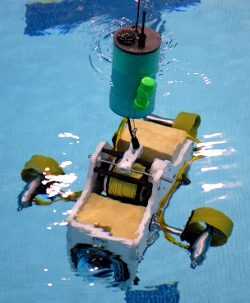

Using real tools, students fabricate the ROVs from PCV pipe, Ethernet cables, electrical components, and computing circuits. They cut and construct the body, build and attach the motors, wire and install the electrical components and control box, and waterproof everything. The Sea Perches are remotely operated or connected via cables to a computer, often with a video game console controller plugged in for operating the vehicle.

The simulated shipwreck in MIT’s Zesiger pool drew students from four schools, each team bringing its own Sea Perch vehicle. At the official run-through June 1, each school was allotted 45 minutes to tackle a different phase of the challenge.

First came 16 high school students from Meridian Academy in Brookline, who employed their ROVs in mapping the wreck scene and surrounding area.

Using Meridian’s maps, Swampscott’s entire 7th grade class — 180 students in total, separated into groups — tested the water for chemicals and marked problem locations.

Next, Rogers High School from Newport, RI, fitted their Sea Perches with grabber robotic arms, which they used to recover cargo containers, starting with the ones Swampscott found to be hazardous.

In the final phase of the mission, students from Minuteman Regional High School in Lexington, Mass., used their Sea Perch ROVs for ship recovery and relocation. Since the Rogers students lightened the load with their cargo recovery operation, the Minuteman students could use their Sea Perches to raise the ship to the surface, and then tow it to shore for salvaging.

Any teacher interested in joining this program should be prepared to put in extra hours and put up with complicated logistics. “It’s a ton of work,” says Andrake. Still, he thinks more such projects are needed. “Educationally, there are no cons as far, as I’m concerned.”

Any teacher interested in joining this program should be prepared to put in extra hours and put up with complicated logistics. “It’s a ton of work,” says Andrake. Still, he thinks more such projects are needed. “Educationally, there are no cons as far, as I’m concerned.”

Rogers teacher Scott Dickinson, like Andrake, a seven-year Sea Grant veteran, praises how the project emulates real science career scenarios. “I particularly liked their program because it focused more on collaborating with the schools” — as opposed to ROV competitions like the MATE Challenge, in which Dickinson and his students also participate. Since the students had to write a proposal to get the funds, and they worked together in the application of science, the project was much more realistic, he says.

To be selected for the program, schools must demonstrate that their administrations support the initiative, and that at least two teachers will be involved. Once schools are selected, Sea Grant provides regular classroom visits, mentoring, workshops and training, cost-sharing of class materials, tours of MIT labs, and opportunities to test vehicles.

To be selected for the program, schools must demonstrate that their administrations support the initiative, and that at least two teachers will be involved. Once schools are selected, Sea Grant provides regular classroom visits, mentoring, workshops and training, cost-sharing of class materials, tours of MIT labs, and opportunities to test vehicles.

Sarah Hammond, Sea Perch Institute Marine Educator and Leader in school outreach, says the program compels students to think abstractly and solve problems. Moreover, “We wanted to make it as approachable as we could,” she says. Those involved with the Institute hope that students will continue studying the concepts they’ve learned and perhaps even pursue careers in such fields as robotics, engineering, and marine sciences.

Filed under: Special Features

Tags: Building robots, Marine engineering, Robotics, U.S. Navy, Underwater Robot