Room to Grow

Indoor ‘vertical farming’ could be an answer to urban food needs and shrinking agricultural space – if cost and energy obstacles can be overcome.

Excerpted from Tom Gibson’s cover story in the March/April 2018 issue of ASEE’s Prism magazine. Click HERE for the full article.

In 1999, Dickson Despommier, a professor of environmental health sciences at Columbia University’s School of Public Health, faced a disappointed group of students. Thinking rooftop gardens might meet the food needs of the world’s rapidly growing urban populations, they had looked into what proportion of Manhattan residents could be fed that way. Answer: 2 percent.

“They said, ‘We’re doomed,’ ” Despommier recounts in a documentary by the Dutch broadcaster VPRO. “I said, ‘What if you took your good idea and made it a better idea by moving a rooftop garden in the building itself?’ ”

With land and water becoming scarce, and rising concern over pesticide and fertilizer use, energy and pollution costs, and transportation, new kinds of agriculture are gaining attention. Among them: A three-dimensional framework in a controlled indoor environment. Coining the term “vertical farm,” Despommier, now professor emeritus, continued to engage students with the idea and in 2010 turned it into a book, The Vertical Farm: Feeding the World in the 21st Century.

Emerging field

The concept is a long way from displacing conventional agriculture, but it has inspired research, start-ups, and pilot projects in the United States, Europe, and Asia, along with imaginative artists’ renderings. “It’s still very much an emerging field where there are not that many commercial operations, especially on a larger scale,” says Neil Mattson, associate professor at Cornell University in the Horticulture Section of the School of Integrative Plant Science in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

With growing consumer demand for locally grown produce, vertical farming draws on specialists in the natural sciences, but also engineers and computer and data scientists. “We need engineers and plant scientists who are excited about this,” enthuses Murat Kacira, (photo, right) a professor in the Department of Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering at the University of Arizona, who worked with a local start-up to turn part of the ill-fated Biosphere into a community vertical farm. “For certain high-value crops and localities and climates, this technology might be economical now. But there is room for improving these vertical farming systems, especially the engineering, because the costs are still really high to operate these systems.”

With growing consumer demand for locally grown produce, vertical farming draws on specialists in the natural sciences, but also engineers and computer and data scientists. “We need engineers and plant scientists who are excited about this,” enthuses Murat Kacira, (photo, right) a professor in the Department of Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering at the University of Arizona, who worked with a local start-up to turn part of the ill-fated Biosphere into a community vertical farm. “For certain high-value crops and localities and climates, this technology might be economical now. But there is room for improving these vertical farming systems, especially the engineering, because the costs are still really high to operate these systems.”

Global pioneers

Overseas, Japan makes an ideal candidate for vertical farming because its terrain is 75 percent mountains, with the bulk of the country’s population concentrated in the remaining 25 percent. Mirai in Tokyo ranks as the world’s largest indoor farm; the former Sony semiconductor factory ships out 10,000 heads of lettuce a day. In the same city, the human resources company Pasona (photo, below) refurbished a 50-year-old building, with one fifth of its 215,000 square feet devoted to growing fruits, vegetables, and rice, according to the online publication Inhabitat. In the crowded city-state of Singapore, Sky Greens claims to be the world’s first low-carbon, hydraulic-driven vertical farm.

In Linköping, Sweden, meanwhile, a firm called Plantagon says it plans to erect a 16-story “plantscraper,” with offices on one side and on the other, a vertical farm in which crops will be grown hydroponically using both LEDs and natural light. The firm recently opened a 65,000-square-foot farm in the basement of a Stockholm office building, according to Huffington Post.

In Linköping, Sweden, meanwhile, a firm called Plantagon says it plans to erect a 16-story “plantscraper,” with offices on one side and on the other, a vertical farm in which crops will be grown hydroponically using both LEDs and natural light. The firm recently opened a 65,000-square-foot farm in the basement of a Stockholm office building, according to Huffington Post.

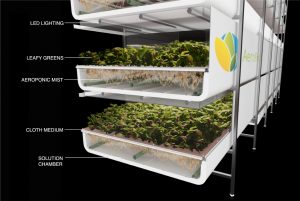

In the United States, one of the fastest-growing ventures is AeroFarms, based in Newark, N.J. The company recently started its ninth farm, billed as the world’s largest vertical farm, at its new global headquarters, and it has others in development in multiple U.S. states and on four continents. (photo, below right)

Vertical Harvest of Jackson in Jackson, Wyo., is one of the world’s first vertical greenhouses. Located on a sliver of vacant land next to a parking garage, the 13,500-square-foot, three-story facility uses a tenth of an acre to grow produce equivalent to five acres of traditional agriculture and supplies it fresh to local grocery stores and restaurants. The top floor grows tomatoes, which require lots of light, while the lower two layers have rotating shelves of leafy greens that get sunlight through windows and artificial light when they’re rotated farther into the building. Working with the University of Wyoming, Vertical Harvest produces 100,000 pounds of produce each year. Racks of plants extend through the floors, so employees can tend to them from each floor.

Across the state in Laramie, entrepreneur Nate Storey launched the vertical farm Bright Agrotech after earning an agronomy doctorate from the University of Wyoming. His company has since been acquired by a Silicon Valley firm, Plenty. (Motto: Can Lettuce Make You Happy?)

Within universities, research on vertical farming falls under controlled environment agriculture (CEA), a term that encompasses both greenhouse produce and plant factory and warehouse-style production. The University of Arizona’s Controlled Environment Agriculture Center (UA-CEAC) recently launched a new two-floor vertical farm known as the UAgFarm for research and to provide experiential educational opportunities for students and educate growers and the public on indoor growing systems. It occupies 750-square-feet with two individually controlled chambers, one on each floor, with two racks, each with two layers of floating, raft-based hydroponic systems. Undergraduate and graduate engineering students designed the systems for it. Other colleges involved with CEA and vertical farming include Cornell, the University of Florida, Ohio State, Michigan State, North Carolina State, MIT, and Purdue.

Based in Milton, Pa., Tom Gibson, P.E., is a consulting mechanical engineer specializing in machine design and green building and a freelance writer specializing in engineering, technology, and sustainability. He publishes Progressive Engineer, an online magazine and information source (www.ProgressiveEngineer.com).

This post was excerpted from the March 2018 cover story of ASEE’s Prism magazine. Click HERE to read the full article [PDF].

Filed under: Special Features

Tags: Aerofarms, Agricultural Engineering, ASEE Prism magazine, botany, Controlled Environment Agriculture, Cornell School of Integrative Plant Science, Dickson Despommier, farm to table, food supply, green infrastructure, greenhouse, Murat Kacira, Neil Mattson, Plantagon, plants, Plenty, Public Policy, Sky Greens, Sustainability, Tom Gibson, University of Arizona, University of Wyoming, urban agriculture, urban farming, vegetables, vertical farms