A Woman Who Made Work Easier

She pioneered the field of ergonomics and time-motion studies, was the first woman elected to the National Academy of Engineering, and received 23 honorary degrees, including from such Ivy League icons as Princeton and Brown. She also raised 12 children, designed the first modern kitchen, and became a resident lecturer at MIT at age 86.

She pioneered the field of ergonomics and time-motion studies, was the first woman elected to the National Academy of Engineering, and received 23 honorary degrees, including from such Ivy League icons as Princeton and Brown. She also raised 12 children, designed the first modern kitchen, and became a resident lecturer at MIT at age 86.

Despite her accomplishments, industrial psychologist and engineer Lillian Moller Gilbreth (her portrait, left, hangs in the Smithsonian) remains best known as the domestic engineer who presided over her family in the beloved children’s classic written by two of her kids: Cheaper By The Dozen.

Despite her accomplishments, industrial psychologist and engineer Lillian Moller Gilbreth (her portrait, left, hangs in the Smithsonian) remains best known as the domestic engineer who presided over her family in the beloved children’s classic written by two of her kids: Cheaper By The Dozen.

“Nothing was considered more of a sin in our house than wasted time and motions,” wrote Frank and his sister Ernestine, who likened family meetings to board meetings.

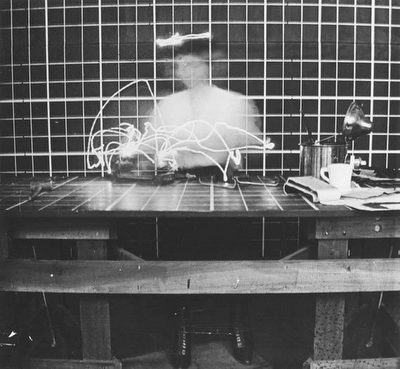

Lillian and her husband, Frank Bunker Gilbreth Sr., invented what is known as motion study. They were the first to use photography to analyze how industrial processes and office tasks were done, breaking down motions into discrete parts to determine how to make a job faster and less fatiguing. [Watch a YouTube video of their original films or a short clip about making a typist’s work easier.] Many of their ideas were tested at home, resulting in the single most efficient way to take a bath and assign age-appropriate chores.

The couple met in Boston in 1903, when Lillian was en route to Europe with her chaperone, Frank’s cousin. They married in 1904, and worked side-by-side from that day forward. She did marketing research for Johnson & Johnson, helped Macy’s department store improve its management department, and worked on ways to encourage better spending decisions by women during the Great Depression.

The couple met in Boston in 1903, when Lillian was en route to Europe with her chaperone, Frank’s cousin. They married in 1904, and worked side-by-side from that day forward. She did marketing research for Johnson & Johnson, helped Macy’s department store improve its management department, and worked on ways to encourage better spending decisions by women during the Great Depression.

Lillian’s legacy includes the “work triangle” and linear layouts that remain standard design features of today’s modern kitchens, according to Slate. She died in 1972, a few years after retiring, at 94.

Read the ASME biography here.

Filed under: Special Features

Tags: Cheaper by the Dozen, ergonomics, Industrial engineering, industrial psychology, Lillian Gilbreth, time motion studies, Women in Engineering