Feature: Bridges and Historical Lessons

by Henry Petroski

This article first appeared in Prism Magazine, October 2006

Engineers design the future; historians analyze the past. These oversimplifications may highlight some fundamental differences between the practice of engineering and history, but when taken as indicative of divergent and exclusionary objectives, they can lead to both inferior engineering and inferior history.

In their enthusiasm for advancing the state-of-the-art by pushing the limits of cutting-edge technology, some engineers do not look back at the history of their field. They do not see it as relevant. Even if they do have an armchair interest in the history of what they are currently engaged in, they tend to compartmentalize that interest or see it as an avocation they will pursue in their retirement.

In their enthusiasm for advancing the state-of-the-art by pushing the limits of cutting-edge technology, some engineers do not look back at the history of their field. They do not see it as relevant. Even if they do have an armchair interest in the history of what they are currently engaged in, they tend to compartmentalize that interest or see it as an avocation they will pursue in their retirement.

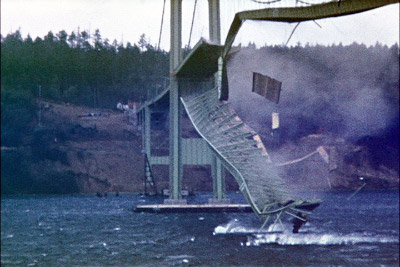

This was the situation among suspension-bridge engineers, especially in the 1920s and ’30s. In a remarkable technological leap, Othmar Ammann designed the George Washington Bridge to have a main span almost double that of the previous record holder. The daringness of this, plus the shallowness of the long deck of the bridge provided a paradigm for subsequent suspension bridge designers to follow. Bridges with less and less stiff decks resulted, culminating in the Tacoma Narrows Bridge that twisted itself apart in a moderate wind.

Image: 1940 Tacoma Bridge collapse, Barney Elliott, Wikipedia.

Filed under: Special Features