Feature: East River Pioneer

Emily Roebling was a proper Victorian wife, determined to remain in her husband’s shadow. Yet, she became a early female pioneer in engineering. Emily Roebling, as much as any single person, was responsible for the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge.

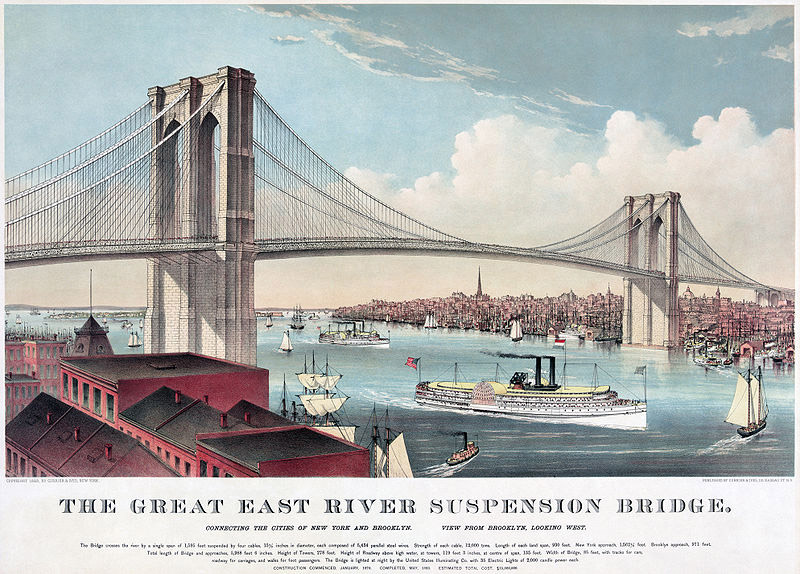

The bridge changed – and took – many lives. Of the estimated 23 people killed during its construction, the most notable was Emily’s father-in-law, John Roebling, who designed it. His foot crushed by metal pilings, Roebling developed lock-jaw from an infection and died. His son Washington, Emily’s husband, then became chief engineer of the largest suspension bridge ever built at the time, and the first structure to span New York’s East River.

As its massive towers began to rise from the riverbed, the bridge brutalized its builders. A new system of pneumatically sealed boxes, called caissons, transported workers to the muddy floor so they could erect the underwater foundations. But when the caisson was raised, workers left the pressurized environment too rapidly. Afterward, they began to suffer from decompression sickness, or “the bends,” a malady little understood at the time. Reactions ranged from cramping to acute physical pain and even blindness and death. Among the stricken was Washington Roebling himself, who became bed-bound and partially blind for the rest of the bridge’s construction.

With a husband ill and near death on many occasions, a brother reeling from an investigation into his Civil War activities, and a young son to raise, Emily took on an additional role: as emissary, passing on to assistant bridge builders the in-depth instructions penned by her husband. When writing became too painful for Washington, Emily transcribed as he dictated each minuscule detail. Eventually, she took over all his important meetings and began visiting the bridge up to three times a day.

Through meticulous work with her husband, Emily studied mathematics, bridge specifications, and the special intricacies of cable construction. When the council that governed the bridge construction demanded that Washington be fired for lack of leadership, Emily ensured that didn’t happen. She also met with politicians, the press, and assistant engineers. Thirteen years after construction began, the bridge opened, and Emily was the first person to cross it, in honor of her contributions. Today, visitors to the East tower of the Brooklyn Bridge can still view the bronze plaque that dedicates the structure to Emily, Washington, and John Roebling – in that order. “Back of every great work we can find the self-sacrificing devotion of a woman,” it states.

In later life, Emily continued to expand her horizons. She drove her own carriage, attended the coronation of the Russian czar, and studied law at New York University. She supported the burgeoning women’s movement. Her final student essay, “A Wife’s Disabilities,” argued for equal legal rights for women. She died of cancer at 58.

————

For more information and resources on the Brooklyn Bridge, see the PBS Website.

Filed under: Special Features

Tags: Bridge building, Brooklyn bridge, Civil Engineering, Emily Roebling, Engineering in History, Suspension bridge, Women in Engineering