Straw Bridges

Activity from TeachEngineering.org, a searchable online library of teacher-tested lessons and activities developed by the Integrated Teaching and Learning Program at the University of Colorado, Boulder’s College of Engineering.

Summary

Working as engineering teams, middle school students design and create model beam bridges using plastic drinking straws and tape. Their goal is to build the strongest truss bridge while meeting the design criteria and constraints, experimenting with different geometric shapes and determining how shapes affect the strength of materials. Let the competition begin!

Grade level: 6-8

Time: 50 minutes

Engineering Connection

Beam bridges are the most common type of bridge designed by engineers and relatively easy to imagine and build. Yet, with truss designs, the possibilities are unlimited. To design bridges, engineers perform careful analysis of bridge geometries and the anticipated applied loads that so they can determine the exact place of the reaction forces. Engineers also consider the most effective materials to achieve a balance of tension and compression. Engineers determine the bridge type, design and materials; analyze site conditions, geologic and environmental factors; and establish detailed design plans and budget/funding schedules.

Learning Objectives

After this activity, students should be able to:

- Describe and design model truss bridges.

- Identify effective geometric shapes used in bridge design.

- Identify several factors that engineers consider when design bridges.

- Follow the engineering design process

Learning Standards

Next Generation Science Standards

- Define the criteria and constraints of a design problem with sufficient precision to ensure a successful solution, taking into account relevant scientific principles and potential impacts on people and the natural environment that may limit possible solutions.

- Evaluate competing design solutions using a systematic process to determine how well they meet the criteria and constraints of the problem.

International Technology and Engineering Educators Association

- Structures rest on a foundation.

- The selection of designs for structures is based on factors such as building laws and codes, style, convenience, cost, climate, and function.

Materials

Each group needs:

- 20 plastic drinking straws (not the bendy type)

- scotch tape

- scissors

- measuring stick or ruler (or one for the class to share)

For the entire class to share:

- small paper cup

- 200-300 pennies (to use as weight)

- wooden support structure (or use two desks)

- balance (for weighing, or count the pennies instead of weighing)

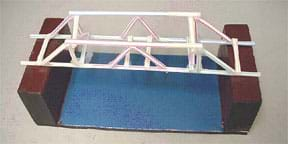

To make the wooden support structure (see Figure 5; optional; may use two desks instead):

- two 7-inch (18-cm) pieces of 2 x 4 wood (for bridge abutments; use scrap 2 x 4s)

- 7 x 13-inch (18 x 33-cm) piece of .25-inch (.6-cm) thick wood (for water base between abutments)

- hammer and nails

- (optional) blue paint for the base of the support structure, to represent water under the bridge

Finished dimensions of the wooden support structure (optional; may use two same-height desks instead). Dimensions may vary from those below, but these particular dimensions can be made by using scrap 2 x 4s. The most important dimension is the inside length or span. The total length should allow for enough space to place the bridge on the “abutments.”

- inside length “span” = 10 inches (25 cm)

- total length (span plus two abutments) = 13 inches (33 cm)

- abutment height = 3.5 inches (9 cm)

- abutment width = 7 inches (18 cm)

Introduction/Motivation

After the Industrial Revolution, bridges became more and more sophisticated as iron and steel became more commonly available. By using iron and steel, engineers could design bridges capable of supporting larger loads and spanning greater distances, making it possible to link cities and communities through shorter, more direct routes and crossing obstacles such as waterways or other natural features that had previously blocked passage. Sometimes we take it for granted that bridges provide important links between places. They enable us to get to resources, conduct commerce, travel and visit other people. The design of bridges is important to the transportation networks we depend upon.

We know there are many different types of bridges. Who can name a type of bridge? (Answers include: Beam, truss, arch, suspension, and cable-stayed.) What makes a bridge a beam bridge? (Review these key points: A beam bridge is usually a simple structure made of horizontal, rigid beams. The beam ends rest on two piers or columns. The beam weight [and any other load] is supported by the columns or piers.) Where on a beam do the forces act? (Review these key points: Compressive forces act on the top portion of the beam and bridge deck, shortening these two elements. Tensile forces act on the bottom portion of the beam, stretching this element.)

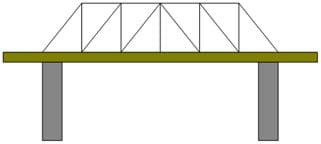

Figure 1. Howe-Kingpost truss design.

© ITL program, College of Engineering, University of Colorado, Boulder

Beam bridges are the most common type of bridges, and include truss bridges. Truss bridges distribute forces differently than other beam bridges and are often used for heavy car and railroad traffic. In a truss bridge, the beams are substituted by simple trusses, or triangular units, that use fewer materials and are simple to build.

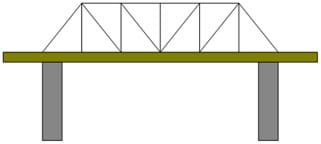

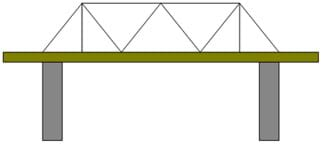

Truss bridge construction rapidly developed during the Industrial Revolution; they were first made of wood, then of iron and finally of steel. During this time, different truss patterns also made great advances. Many truss systems originated in the mid-1800s are still in use today. The Howe Truss, one of the more popular designs, was patented by William Howe in 1840. His innovation was his use of vertical supports in addition to diagonal supports (see Figure 1). The combination of diagonal and vertical members created impressive strength over long spans; this made the truss design ideal for railroad bridges. Howe’s truss was similar to the existing Kingpost truss pattern. However, he used iron for the vertical supports and wood for the diagonal supports. Although iron and wood are not used as much today in modern bridges, the Howe Truss pattern is still widely used. See Figures 2-4 for other truss patterns.

Today, we are going to act as teams of engineers making bridge models. We have been hired by a city to create a bridge to cross one of the local rivers. However, the city does not want the bridge to affect the fish population in the river below it. Engineers always consider the design objective when creating models. Our design objective is to make a bridge that spans the river (scaled down to a distance of 10 inches [25 cm], supports the most weight for the cars that will pass over it, and does not disturb the river’s fish. To simulate the load of the cars, our bridge must have a place to securely hold a small cup in the center of the span. To demonstrate environmental limitations on the design, no part of the bridge may touch the “water” (or bottom of the wooden support structure) and the bridge cannot be taped to the wooden support structure. Engineers often have many design constraints or limitations that are part of their job assignments. Today, our design constraints not only include the environmental and weight constraints, but also limited budget and materials using straws and tape as our construction materials.

Procedure

Before the Activity

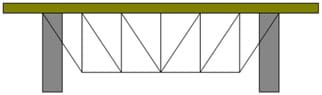

Figure 5. Wooden support structure for the testing station. Blue represents the water below the bridge. The end blocks represent bridge abutments.

© ITL program, College of Engineering, University of Colorado, Boulder

- For bridge testing, make a wooden support structure (see Figure 5; optional), or place two desks ~10 inches (25 cm) apart.

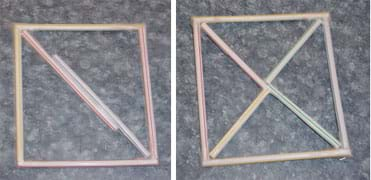

- Gather materials and make example square and triangle shapes with tape and straws as shown in Figures 6 and 7.

- Divide the class into groups of two students each.

With the Students

- Discuss truss bridges with students. Ask students to vote by a show of hands to the following question, “Which shape is more stable, triangles or squares?” Tally their responses and write the totals on the classroom board. Explain with visual demonstrations that squares are less stable than triangles. Do this by showing example straw shapes similar to those in Figures 6 and 7. Stand the shapes up on a desk and push down on the top of them. With very little force applied, the open square shape twists, while the square shape composed of inner triangles withstands much more force.

- To each team, pass out 20 straws, scotch tape, scissors and a ruler. Remember, you are teams of engineers making model bridges using straws and tape as your construction materials. Think carefully about what your design will look like. The design objective is to make a bridge that spans the river and supports the most weight. Your bridge design must span a distance of 10 inches (25 cm), which means that the bridge must measure longer than that so it can rest on the abutments on each side of the river. Your bridge must have a place to securely hold a small cup in the center of the span. When we test your bridge, pennies will be added to the cup until the bridge collapses. That amount of pennies and its cup will be weighed. Other design constraints to consider are that no part of the bridge may touch the “water” (or bottom of the wooden support structure) and the bridge cannot be taped to the wooden support structure. Also, the materials are limited. While you can cut your straws to any length you want, you will not be given any additional (or replacement) straws even if you accidentally cut them to lengths you don’t want. So, think, sketch and measure before you cut. Another point to make: A bundle of straws taped together does not satisfy the “spirit” of this bridge-building activity. However, it is not necessary to have bridges look as if small cars could go over them. If necessary, show students example truss designs (see Figures 1-4) as examples of the approach to take (not to copy).

- Give the student teams time to create their bridges. Give students time to brainstorm ideas, draw sketches, and make plans and calculations before doing any cutting and taping with their limited number of straws.

- Before strength testing the bridges, ask each team: Predict how much weight you think will make your bridge collapse. Record predictions on the board. Place each bridge on the wooden support structure (see Figure 8). Position a small paper cup on the bridge at the center of the span; do not place the cup at any other location. Gradually fill the cup with pennies until the bridge collapses or the cup falls off (see Figure 9). Weigh the cup and the pennies on the balance. Make a note of this weight, and record it on the board next to its prediction. Repeat to test all bridges. Note, it may be helpful to add a lot of pennies quickly at first until it appears that the bridge is beginning to fail. At that point, add fewer pennies at a time, more carefully and slowly. The winning bridge design is the one that supports the most weight, while meeting the design criteria and constraints.

- Conclude by leading a class discussion of the bridge strength testing results. How would they improve their bridge design? Have students from each engineering team describe what they would do to make their bridges stronger.

Safety Issues

Remind students of scissor safety rules.

Troubleshooting Tips

- Use plastic straws that are not the flexible or “bendy neck” type. If only flexible type straws are available, cut off the straw ends that contain the flexible sections. Since this reduces the straw length, give students 25 straws per group.

- Using a balance to calculate the weight of the pennies in the cup is a quick method to determine how much weight each straw bridge held before it collapsed. If a balance is not available, count the number of pennies for weight comparison.

- If rulers are not available, measure the span by marking its width on another piece of paper as a handy reference. Or, explain how students can obtain simple measurements using full sheets of copy paper (8 ½ x 11 inches). For example, with a 10-inch span, it would be desirable to make the bridge about 11 inches or equal to the longer dimension of the paper.

Assessment

Pre-Activity Assessment

Voting & Demo: Ask students to vote by a show of hands their opinions to the following question. Tally the votes and write the totals on the classroom board.

- Which shape is more stable: triangles or squares? (Explain with visual demonstrations that squares are less stable than triangles. Stand some example tape and straw shapes [Figures 6 and 7] on a desk and push down on the top of them. With very little force applied, the empty square shape twists, while the square shape composed of inner triangles withstands much more force.)

Activity Embedded Assessment

Prediction: Before testing, ask teams to predict how much weight will collapse their bridges. Record predictions on the board.

Post-Activity Assessment

Re-Engineering: Ask students how they might improve their bridge designs, and have them sketch or test their ideas.

Activity Extensions

Ask students if they know about the engineering design process. It is the design, build and test loop used by engineers around the world. The steps of the design process include: 1) define the problem, 2) come up with ideas (brainstorming), 3) select the most promising design, 4) communicate the design, 5) create and test the design, and 6) evaluate and revise the design. Have students reflect upon the bridge-making activity and list what they did for each step of the design process.

Truss patterns are used for more than bridge design. Ask students to note all the real-world applications in which they see truss systems used during one week. Possible examples: the structural members found in roofs (look up into your garage or basement), floors, ceilings and construction of other structures, plus ramps, radio towers, crane arms, and components of other types of bridges. Even a geodesic dome is considered a truss in the shape of a sphere. Can you see triangle geometry in the shape of a bicycle frame? Have students report back to class to share their findings.

Activity Scaling

- For lower grades, as students design and build straw bridges to span 10 inches (25 cm), permit them to place intermediate supports in the “water.”

- For higher grades, have students design and build straw bridges to span a distance of 20 inches (50 cm) using the same amount of material and no intermediate supports in the “water.”

Contributors

Jonathan S. Goode; Joe Friedrichsen; Natalie Mach; Chris Valenti; Denali Lander; Denise W. Carlson; Malinda Schaefer Zarske

Acknowledgements

This digital library content was developed by the Integrated Teaching and Learning Program under National Science Foundation grant no. 0338326. However, these contents do not necessarily represent the policies of the National Science Foundation, and you should not assume endorsement by the federal government.

Last modified: August 15, 2017

Filed under: Class Activities, Grades 6-8, Lesson Plans

Tags: bridge, Bridge Design, Class Activities, Engineering Design Process, forces, Grades 6-8, Lesson Plan, truss